Every product decision involves negotiation. You negotiate with engineering about timelines, with stakeholders about priorities, with customers about requirements, and with your team about trade-offs. Most product leaders approach these conversations as battles to win. That’s why they fail.

The Harvard Negotiation Method offers a better approach. “Getting to Yes” by Roger Fisher and William Ury from the Harvard Negotiation Project introduced principled negotiation in 1981. The framework remains relevant because it solves a fundamental problem: how to get what you need without damaging relationships or leaving value on the table.

Why Positional Bargaining Fails in Product Teams

Traditional negotiation operates on positional bargaining. One side wants the deliverable done in three months, the other says six months. You meet in the middle at four and a half months, and everyone feels like they lost something.

This approach fails for several reasons. First, it anchors everyone to arbitrary positions rather than actual needs. Second, it creates adversarial dynamics that poison ongoing relationships. Third, it produces suboptimal outcomes because you compromise on positions instead of solving for underlying interests.

In product development, you can’t afford this. You work with the same engineers, stakeholders, and customers repeatedly. Burning bridges to win a single negotiation undermines your ability to work effectively with these people again.

The 4 Core Principles of the Harvard Negotiation Method

The Harvard Negotiation Method restructures how you approach any negotiation to “get to yes” through four core principles.

Principle 1: Separate People from the Problem

When your engineering lead pushes back on a deadline, your instinct might be to see them as difficult or uncooperative. That framing guarantees conflict.

The principle here is straightforward: the person across from you is not your problem. The actual problem is the gap between what you both need to achieve. Attack the problem together instead of attacking each other.

Practically, this means being explicit about the separation. Instead of saying “You’re always pushing back on deadlines,” try “I know we both want to ship a quality product. Let’s figure out what’s making the current timeline feel impossible.”

Principle 2: Focus on Interests, Not Positions

A position is what someone says they want. An interest is why they want it.

When a stakeholder demands a specific feature be included in the next release, that’s a position. Their interest might be satisfying a key customer, hitting a revenue target, or addressing competitive pressure. Once you understand the interest, you can often find better solutions than the stated position.

Ask “What problem does this solve for you?” or “What happens if we don’t do this?” These questions reveal the underlying interests and open up the solution space.

Principle 3: Generate Options for Mutual Gain

Most negotiations fail because people assume a fixed pie. If you get more, I get less. This mindset stops you from finding creative solutions.

Before deciding on any solution, invest time in generating multiple options. Brainstorm without committing. The goal is to expand possibilities before narrowing them down.

For example, if engineering says they need six months and you need delivery in three, don’t immediately compromise. Explore: Could you ship a reduced scope in three months? Could another team handle part of the work? Could you staff up temporarily? Could you shift other projects to free up capacity?

The best solutions often emerge from this exploratory phase, but only if you resist the pressure to settle quickly.

Principle 4: Insist on Objective Criteria

When you can’t find a solution that satisfies everyone’s interests, you need a fair standard for deciding. That standard should be independent of either party’s will.

Instead of arguing about whether a product enhancement should take three or six months, look at comparable products, industry benchmarks, or expert estimates. Instead of debating feature priority based on opinions, reference user research data, business metrics, or strategic objectives.

Objective criteria shift the conversation from a contest of wills to a joint search for a fair answer. It’s no longer about who has more power or stubbornness. It’s about what’s reasonable given the facts.

Understanding BATNA: Your Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement

The most powerful concept in “Getting to Yes” is BATNA: Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement. Understanding your BATNA transforms how you approach any negotiation. Your BATNA is what you’ll do if this negotiation fails.

Knowing your BATNA gives you clarity on when to walk away. If your BATNA is strong, you negotiate from confidence. If it’s weak, you know you need to be more flexible or work to improve your alternatives before negotiating.

Before any significant negotiation, ask yourself: What will I do if we don’t reach agreement? The answer tells you how much flexibility you actually have.

Equally important is understanding the other party’s BATNA. If engineering’s alternative to agreeing on your timeline is being assigned to a different product they find less interesting, that affects their negotiating position. If a customer’s alternative to your product is a strong competitor, that affects theirs.

4 Negotiation Mistakes Product Leaders Make

The most common mistake is treating every negotiation as a one-time transaction. You optimize for winning the immediate discussion and damage the relationship for future collaboration.

Another frequent error is starting with positions instead of interests. You walk into a meeting having already decided on the solution, then try to convince everyone else. You’ve skipped the most valuable part of the process.

Product leaders also tend to underinvest in the option-generation phase. You might briefly consider alternatives, but you don’t create the space for genuine exploration. This means you miss better solutions that would have satisfied everyone more fully.

Finally, many leaders negotiate without knowing their BATNA. They enter discussions with vague discomfort about the other party’s position but no clear understanding of their alternatives. This puts them at a significant disadvantage.

Understanding these mistakes makes it easier to avoid them. Here’s how to prepare for your next negotiation using principled negotiation.

How to Prepare for Your Next Negotiation

Start with one upcoming negotiation. Before that conversation, write down:

- What problem are we actually trying to solve (separate from the people)?

- What are my real interests, not just my opening position?

- What might their interests be?

- What’s my BATNA if this negotiation fails?

- What objective criteria could we use to evaluate options?

Then in the conversation, focus on understanding their interests before proposing solutions. Spend real time generating options together. Reference objective criteria when you disagree.

This approach feels slower initially. It is slower. But it produces better outcomes and preserves relationships that matter for long-term success.

Mastering Negotiation as a Product Leader

These principles work whether you’re negotiating your own interests with stakeholders and engineering teams or helping team members resolve their conflicts. While this post focused on direct negotiation, applying these same principles to team facilitation requires different techniques.

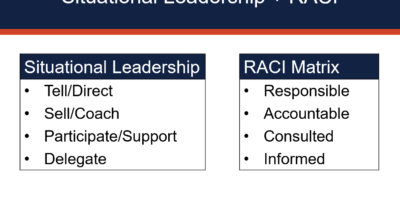

Our Building High-Performing Teams Workshop teaches you how to apply these negotiation principles when facilitating conflicts between team members, alongside other proven frameworks for psychological safety, decision authority, and team alignment.

Related Reading

Product Team Conflict Management: Turn Tension Into Innovation – Learn how the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument helps you choose the right conflict approach for different situations.