You’ve seen it happen. A team that nails predictable work completely falls apart when facing something unprecedented. Or a leader who excels at crisis management tries to apply that same urgency to stable operations and creates chaos.

The problem isn’t capability. It’s context blindness.

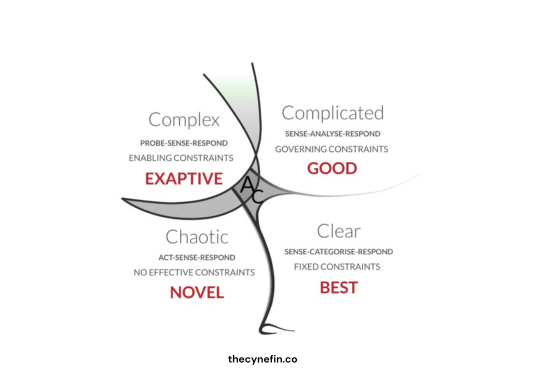

Most leaders treat all problems as if they require the same approach. The Cynefin framework, developed by Dave Snowden when he worked at IBM, gives you a way to diagnose what kind of problem you’re actually facing before you decide how to solve it. This sense-making framework helps product leaders and their teams match their problem-solving approach to the complexity of the situation.

What Is the Cynefin Framework? Understanding the Five Domains

Cynefin (pronounced kuh-NEV-in) identifies five distinct contexts for problem solving. Four outer domains represent different types of problems. The center represents two specific states: aporetic (legitimate uncertainty or paradox) and confused (misdiagnosis of which domain you’re in).

The Clear Domain: When Best Practices Apply

These are problems where cause and effect are obvious. The relationship is stable and repeatable.

In product development, this includes established processes: deploying code through your CI/CD pipeline, running standard QA checks, or following your security review protocol.

The approach here is sense-categorize-respond. You assess the situation, match it to a known category, and apply the established best practice. This is where efficiency matters. Document your processes, train people on them, and measure compliance.

The constraint type here is fixed. Things must be done in a certain way in a certain order. When these constraints work, they create predictability. When they break, they can break catastrophically.

The Complicated Domain: When Expertise Drives Solutions

Here, cause and effect exist, but they’re not immediately obvious. You need expertise to figure out the right answer.

Think about performance optimization, technical architecture decisions, or analyzing why a feature isn’t converting as expected. There’s no single best practice because the right answer depends on context and analysis. Multiple good practices might exist, and experts could legitimately disagree on the best approach.

The approach is sense-analyze-respond. Assess the situation, bring in experts to analyze it, and choose from the good options they identify. This is where your senior engineers and product strategists earn their keep.

The constraint type here is governing. Think of these as rules or policies that provide boundaries but allow for judgment and expertise within those boundaries.

The mistake leaders make here is either treating complicated problems as if they’re clear (applying best practices without analysis) or as if they’re complex (running experiments when expertise could provide answers).

The Complex Domain: Where Experimentation Reveals Answers

Cause and effect only become clear in hindsight. The system is unpredictable, and expertise alone won’t tell you what will work. Neither best practices nor good practices apply here because you don’t yet know what works.

New product development often sits here. You’re exploring user behavior you don’t fully understand, building in markets that are evolving, dealing with emergent patterns you couldn’t have predicted.

The approach is probe-sense-respond. Run small experiments, see what happens, and amplify what works. This is where MVP thinking, rapid iteration, and learning cycles matter. Teams using Scrum understand this intuitively because Scrum embraces changing requirements as a natural part of discovery.

The constraint type here is enabling. These constraints allow the system to function but don’t control the entire process. They create the conditions for patterns to emerge without dictating what those patterns will be.

Most product failures happen because leaders try to plan and analyze their way through complexity. They want comprehensive requirements and detailed roadmaps for situations where those tools don’t apply. You can’t analyze your way to certainty when you’re dealing with a complex system. You discover what works through experimentation, not by applying established practices.

The Chaotic Domain

No clear cause and effect relationship exists. The situation is too turbulent for pattern recognition. There are no constraints.

This is your production outage affecting thousands of users. A flash crash is triggering panic selling across your platform. A security breach is actively compromising customer data.

The approach is act-sense-respond. Stabilize the situation first, then assess, then work toward a response. Speed matters more than perfection.

The error here is trying to understand before acting. In chaos, you need to establish order before you can make sense of anything. Your goal is to stabilize the situation so you can then diagnose which domain you’re actually dealing with.

The Center: Aporetic and Confused States

The center domain has two aspects: aporetic and confused.

Aporetic refers to legitimate uncertainty. You’re facing contradictions or paradoxes that can’t be resolved immediately. You know what you don’t know, and you need to sit with that uncertainty while you gather evidence.

Confused refers to misdiagnosis. You think you’re in one domain when you’re actually in another. This happens when bias, habit, or habitual thinking patterns prevent you from seeing the situation clearly.

When you can’t determine which domain applies, breaking down the problem into smaller pieces often helps. Each piece might belong in a different domain.

The Catastrophic Fold: Why Clear Domains Can Collapse Into Chaos

The boundary between clear and chaotic is different from the others. It’s represented as a cliff or catastrophic fold.

When you’re operating in the clear domain with established best practices, complacency becomes a risk. You stop questioning whether the context has changed. You miss warning signals. You assume what worked yesterday will work tomorrow.

Then something shifts. The best practice no longer applies. But you’re so confident in your established approach that you don’t notice until you’ve walked off the cliff into chaos.

This is why stable operations require active sensing. Even when cause and effect seem obvious, you need to challenge assumptions and watch for changes. The alternative is a sudden, catastrophic drop into chaos with no easy way back up.

Why the Cynefin Framework Matters for Product Leaders

The framework gives you language to explain why different situations need different approaches.

Your engineering team wants to spend three weeks planning a feature for a nascent market. You can point out that you’re in the complex domain. Planning won’t reduce uncertainty. Small experiments will.

Someone wants to analyze root cause during an active crisis. You can name that you’re still in chaos and need to stabilize before analyzing.

The framework also prevents a common leadership trap: applying your preferred approach to every situation. Leaders who are good at analysis try to analyze everything. Leaders who excel in crisis mode try to make everything urgent. The framework forces you to match your approach to the context.

Common Mistakes When Using the Cynefin Framework

The biggest mistake is trying to make everything clear. Leaders who want predictability try to impose it on complex and complicated situations. This shows up as excessive planning, rigid processes, and frustration when reality doesn’t conform to the plan. Understanding the risks of waterfall development illustrates what happens when you apply clear-domain thinking to complex problems.

The opposite mistake is treating everything as complex. Some leaders are so comfortable with experimentation and emergence that they skip best practices where they apply and overanalyze what should be straightforward.

Another trap is staying too long in one domain. What you learned through experimentation (complex) should eventually become established practice, though not everything becomes clear domain. If you’re still experimenting with something you figured out a year ago, you’re not learning. You’re just avoiding commitment.

The most dangerous trap is not recognizing when you’ve moved from clear to chaotic. By the time you realize the old rules no longer apply, you’ve already fallen off the cliff.

Take the Next Step

Understanding the Cynefin framework is valuable. Applying it systematically across your organization creates competitive advantage.

Our Building High-Performing Organizations workshop gives you practical tools to diagnose organizational challenges using Cynefin alongside frameworks for culture, structure, governance, and leadership. You’ll learn to recognize which which systems need adaptation as problems shift between domains and leave ready to match your organizational responses to the actual complexity you face.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Cynefin Framework

What does Cynefin mean?

Cynefin is a Welsh word (pronounced kuh-NEV-in) that roughly translates to “habitat” or “place.” It represents the multiple factors in our environment and experience that influence us in ways we can never fully understand.

Who created the Cynefin framework?

Dave Snowden developed the Cynefin framework while working at IBM’s Institute for Knowledge Management in 1999. He has continued to evolve the framework through his work in complexity science and organizational management.

When should I use the Cynefin framework?

Use the Cynefin framework when you need to diagnose what type of problem you’re facing before choosing your approach. For example, when your team debates whether to build a detailed architecture plan or start with a prototype, Cynefin helps you identify whether you’re in complicated territory (where analysis helps) or complex territory (where experimentation wins). It’s also valuable when standard practices aren’t working or when you need to explain why different situations require different responses.

How is Cynefin different from other frameworks?

Traditional management frameworks assume all problems follow the same process and try to impose linear thinking on every situation. Cynefin recognizes that different problem types require fundamentally different approaches. It’s a sense-making and diagnostic tool rather than a prescriptive methodology. Where other models tell you what to do, Cynefin helps you diagnose which methodology fits your specific situation.

Can a problem move between Cynefin domains?

Yes. Problems regularly shift between domains as you learn more, as circumstances change, or as practices stabilize. Recognizing these shifts is critical to adapting your approach effectively.

For additional perspective on dealing with complex team dynamics, explore the A-CSM training or the Building High-Performing Team Workshop.