Product managers, team leaders, and development teams make hundreds of decisions every week. Which features to prioritize, what user feedback to act on, how to interpret analytics data, when to pivot strategy or stay the course. We believe these decisions are rational, data-driven, and objective, but they rarely are.

Your brain relies on mental shortcuts when processing information. These shortcuts, called heuristics, help you make quick decisions without analyzing every detail. Sometimes they work efficiently. Other times they create systematic errors in judgment. These predictable patterns of flawed thinking are cognitive biases, and in product development, they cause teams to misinterpret data, dismiss valuable feedback, and make expensive mistakes.

Understanding cognitive biases won’t eliminate them from your decision-making process. 2However, awareness helps you build better systems and catch yourself before small errors become major failures.

The Big Three: Biases That Distort Every Decision

Three cognitive biases show up more frequently than any others in product work. They operate at different stages of decision-making, and together they create a powerful distortion field around how you understand your users and your product.

Confirmation Bias: Building Products for Imaginary Users

You’re convinced users need a faster workflow. During user interviews, you notice every comment about speed while overlooking feedback about clarity and learning curves. After launch, you emphasize metrics showing faster task completion while minimizing data on increased error rates.

This is confirmation bias in action. You search for, interpret, and remember information that confirms what you already believe. It operates at every stage: which questions you ask in research, what data you collect, how you interpret results, and what you remember afterward.

The problem isn’t that you’re deliberately ignoring contradictory evidence. Your brain does it automatically. Research by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who introduced the concept of cognitive biases in 1972, showed that even trained scientists fall prey to confirmation bias in their own research. Product teams are no exception.

This bias shows up when user research validates assumptions instead of testing them, when you cherry-pick metrics supporting your position in prioritization debates, when you remember feedback that aligned with your vision while forgetting challenges to it. You end up building products for the users you imagine rather than the users you have.

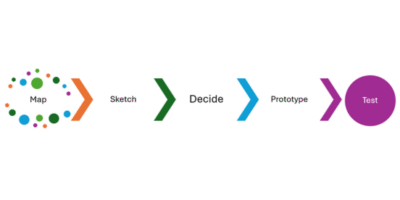

What to do about it: Actively seek evidence that contradicts your assumptions. During user research, spend at least as much time exploring where you might be wrong as you do validating what you believe. Ask someone who disagrees with your decision to articulate the strongest case for the opposite approach. Review failure metrics alongside success metrics. Better yet, track what would disprove your hypothesis, not just what supports it. Use systematic product discovery techniques like prototyping and usability testing to ground decisions in evidence rather than assumptions.

Anchoring Bias: When First Opinions Become Immovable Truth

Your team estimates how long a feature will take to build. The first developer says “probably two weeks.” Even when others suspect it will take longer, their estimates cluster around that initial number. Welcome to anchoring bias.

You rely too heavily on the first piece of information you encounter. In product work, this shows up constantly. Initial prototypes shape all future iterations even when better approaches emerge. Early revenue projections become immovable targets regardless of market feedback. First user comments carry disproportionate weight compared to later data, even with larger sample sizes.

The first number, first opinion, or first solution creates an anchor that pulls all subsequent thinking toward it. Pricing gets set based on competitor prices you saw first rather than value or willingness to pay. Project scope gets determined by initial gut feelings that become fixed baselines. Early success metrics frame how you interpret all subsequent data.

What to do about it: Gather estimates and opinions independently using facilitation techniques like silent writing or 1-2-4-All before team discussions. When pricing or scoping projects, deliberately examine multiple reference points before settling on one. Create calendar reminders to revisit early assumptions explicitly as you learn more. Use planning poker or similar techniques that prevent the first voice from anchoring the entire conversation.

Availability Bias: Why the Loudest Voice Wins

Six months ago, a major customer churned after a catastrophic data migration failure. The story is legendary in your company. Engineers still talk about the all-hands meeting, the post-mortem, the lessons learned. Now, every time someone proposes a database change, that story comes up. You find yourself being overly cautious about technical decisions that have nothing to do with data migration, while ignoring other risks that are statistically more likely but less memorable.

Availability bias makes you overweight information that’s vivid, dramatic, or easy to recall. The catastrophic failure feels more important than the hundred quiet successes. The bug affecting your CEO gets prioritized over bugs affecting hundreds of regular users. The horror story someone told you about microservices keeps you from considering whether they might actually solve your scaling problems.

Your decision-making ends up distorted by whatever’s most memorable rather than what’s most important. You build features for edge cases because those stories stick in your mind. You avoid potentially good solutions because of vivid negative examples.

What to do about it: Build systematic feedback collection that captures the silent majority, not just vocal or dramatic incidents. When someone raises an issue in meetings by telling a compelling story, make it a habit to ask how frequently it actually occurs and look at the data before responding. Track metrics that surface patterns rather than relying on memorable anecdotes. Create dashboards that show you what’s statistically significant, not just what’s emotionally resonant.

The Expert’s Paradox: When Experience Becomes Liability

Overconfidence Bias: Success Breeds Blind Spots

Your team has deep domain expertise. You’ve shipped dozens of features successfully. You know your users. When someone suggests usability testing on a new interface, you dismiss it. The design is obviously intuitive. You know what users want. Testing would just slow down delivery.

Then you launch, and adoption is terrible. Users find the interface confusing for reasons you never anticipated. What happened?

Overconfidence bias makes you overestimate your knowledge, abilities, and the precision of your beliefs. The cruel irony is that experts often exhibit more overconfidence than novices. Expertise in one area creates a false sense of expertise in related areas. Past success breeds confidence about future outcomes. You become so good at your job that you stop questioning whether you might be wrong.

You skip validation because you’re confident in your understanding. You make precise predictions about adoption or revenue without acknowledging the massive uncertainty involved. You dismiss risks and edge cases that seem unlikely. You don’t prepare contingency plans because you’re certain about how things will unfold.

What to do about it: Express all predictions as ranges rather than point estimates. Track your prediction accuracy over time and review it quarterly (most teams find they’re far less accurate than they believed). Involve people outside your team who don’t share your context or expertise. Remember that confidence is a feeling, not evidence. In fact, make this your rule: the more confident you feel, the more you should actively seek disconfirming evidence through validation techniques like prototyping and usability testing. Your gut might be right, but it’s worth checking.

Pro-Innovation Bias: When New Equals Better

Your team gets excited about a new technology. It’s faster, more elegant, and solves several technical problems you’ve been facing. You decide to rewrite a core system using this approach. Months in, you realize the new technology introduced different problems you didn’t anticipate, and the benefits aren’t as large as expected. But you’ve already invested too much to turn back easily.

Pro-innovation bias makes you overvalue the benefits of new approaches while undervaluing their costs and limitations. You focus on what new technology or methods will improve while glossing over what they’ll make worse or what you’ll have to give up. The bias shows up when evaluating new frameworks, architectural patterns, development methodologies, or feature ideas.

The technology industry amplifies this bias. Conference talks celebrate the new. Blog posts showcase cutting-edge approaches. Hiring managers want experience with the latest tools. This creates pressure to adopt innovations not because they solve your specific problems, but because staying with proven, boring technology feels like falling behind.

You chase new technologies before they’re mature enough for production use. You adopt new practices that solve one problem while creating three others you didn’t foresee. You underestimate migration costs, learning curves, and the hidden complexity of new approaches. You build features because they’re technically interesting rather than because they’re valuable to users.

What to do about it: For every benefit a new approach offers, force yourself to articulate what it makes worse or what you’ll lose. Require small proofs of concept before large investments. Talk to people who’ve tried the innovation and ask specifically about unexpected downsides, not just success stories. Remember that boring, proven technology usually beats exciting, new technology for production systems. New isn’t inherently better, it’s just new.

How You Learn the Wrong Lessons

Outcome Bias: When Results Justify Terrible Processes

Your team shipped a feature with minimal research and testing. The approach was risky and poorly planned. But it succeeded in the market. In the retrospective, everyone agrees it was a smart decision. Six months later, someone proposes a similar approach for a different feature. The previous success gets cited as evidence this strategy works.

Outcome bias makes you evaluate decisions based on results rather than the quality of the decision-making process at the time. A bad decision that worked out becomes a good decision in your memory. A well-reasoned decision that didn’t work out becomes labeled a mistake.

This creates a vicious cycle. You repeat risky approaches that happened to work once. You avoid thoughtful methods that happened to fail once. You learn the wrong lessons from both successes and failures. Most damaging, you make it impossible to improve decision-making processes because you only evaluate based on outcomes.

What to do about it: In retrospectives, force yourself to separate two questions: “Was this a good decision given what we knew at the time?” from “Did this turn out well?” Document your reasoning before you know outcomes. Recognize explicitly that good decisions sometimes fail due to factors outside your control, and bad decisions sometimes succeed due to luck. If you can’t separate process from outcome, you’ll never improve your process.

Conservatism Bias: Ignoring Evidence That You’re Wrong

You launch a major feature based on extensive research showing users want it. After launch, usage data shows terrible adoption rates. But instead of reconsidering the feature, you decide users just need more education. You create campaigns, update documentation, add tooltips. Data keeps showing poor adoption, but you keep finding reasons why the original research was still valid.

Conservatism bias makes you underweight new information that contradicts existing beliefs. You spent months researching this feature. You got leadership buy-in. You told customers it was coming. The sunk costs are enormous, both financial and emotional. Admitting it’s not working feels like admitting you were wrong about everything, so you find reasons to discount the evidence.

You persist with failing features longer than you should. You dismiss market changes that threaten your strategy. You update products slowly in response to competitor moves or technology shifts. You interpret ambiguous data in ways that preserve existing beliefs.

What to do about it: Establish clear success criteria before launching features and commit in advance to acting on what the data shows. Separate the decision to build something from the decision to keep it. Schedule regular check-ins specifically to review whether your initial assumptions still hold. Build kill criteria into feature launches and actually use them.

The Timing Trap: When Recency Distorts Reality

Your quarterly planning meeting runs three hours. You methodically evaluate five different initiatives, reviewing data and discussing trade-offs for each one. The person who speaks last makes a solid but unremarkable case for their project. Nothing particularly memorable, just a clear articulation of the problem and proposed solution.

You leave the meeting convinced it should be the top priority, even though by objective measures, the second initiative you discussed had stronger business impact and clearer customer demand. What happened? The last thing you heard is dominating your thinking.

Recency bias makes you overweight information encountered recently while underweighting older information, even when the older information is more relevant or reliable. The last user interview feels more important than the fifty that came before it, regardless of what was said. The most recent sprint feels representative of team velocity, even though three months of data shows a different pattern. This quarter’s results overshadow clear long-term trends that should guide your strategy.

Your roadmap reflects recent feedback instead of systematic prioritization. You make hiring decisions based on the last few candidates instead of the entire pool. You change strategy based on recent results without considering whether you’re reacting to noise or signal. The last person to speak in meetings has disproportionate influence on decisions.

What to do about it: Review data over consistent time periods, not just recent snapshots. In meetings, capture all arguments in writing so early contributions aren’t forgotten by the end of discussion. Randomize the order of presentations when comparing options. Make final decisions after meetings, not during them, giving yourself time to consider all options with equal weight.

The Biases You Don’t See

Several other biases deserve brief mention because they show up regularly in product work, even if less frequently than the major ones above.

The ostrich effect describes avoiding information that might be uncomfortable. Your North Star metric has declined for three weeks, but you don’t mention it in standups. You focus on secondary metrics that look better. Problems compound because you don’t address them early when they’re still manageable. Create forcing functions that make bad news visible and build a team culture where surfacing problems early is rewarded rather than punished.

The clustering illusion makes you see patterns in random data. Three enterprise customers request similar features in the same week, and you immediately start planning a major initiative to serve this segment. But those three requests might be coincidence, not a trend. Require minimum sample sizes before acting on patterns. When you spot a pattern, explicitly test the hypothesis that it might be random.

Information bias is the tendency to seek information even when it won’t change your action. Your team debates between two approaches for weeks, gathering more data that never clearly favors either option. Before gathering more information, articulate what decision it will inform and what you’ll do based on different outcomes. If additional data won’t change the decision, stop gathering it. For many decisions, building something small and learning from real usage beats researching indefinitely.

Bandwagon effect drives you to adopt practices because many others have. Every few years, a new approach sweeps through the technology industry (microservices, React, mobile-first, Agile), and companies adopt it not because it solves their specific problems but because everyone else is doing it. When someone proposes adopting a practice because “everyone’s doing it,” stop and articulate the specific problem you’re trying to solve first.

The bias blind spot is perhaps the most insidious. You probably think you’re less biased than your colleagues. Product managers think engineers are too conservative. Engineers think product managers chase shiny objects. Everyone thinks they’re the rational one in the room. When you’re certain you’re right and others are wrong, that’s exactly when you should slow down and examine your reasoning.

Building Decision-Making Systems That Work

You can’t eliminate cognitive biases through awareness alone. Your brain will keep using these shortcuts because they’re efficient most of the time and deeply embedded in how humans process information. The solution isn’t to become perfectly rational. It’s to design systems and processes that counteract bias.

Diverse teams catch more biases than homogeneous ones because people have different blind spots and experiences. When everyone has the same background, you all share the same blind spots. Structured decision-making frameworks reduce the impact of whichever bias is most salient at the moment. Using group decision-making techniques like fist-of-five or Roman voting prevents anchoring bias and ensures everyone’s input gets weighted appropriately. Data collection systems that don’t depend on human memory counteract availability and recency bias. Requiring explicit articulation of assumptions makes confirmation bias visible to others on the team.

Start small. Pick one or two biases you recognize in your team’s recent decisions. Maybe you’ve noticed the team anchoring on early estimates, or maybe you’ve caught yourself dismissing data that contradicts your product vision. Build simple processes to counteract those specific biases. Document what works and what doesn’t. Then expand from there.

The goal isn’t perfect rationality in every product decision. It’s building products based on evidence and sound reasoning rather than the quirks of human psychology. Every bias you recognize in your decision-making is a mistake you can avoid and a better product you can ship.

Your users won’t know you’re fighting cognitive biases in your product development process. They’ll just notice you’re building better products that solve their actual problems.

Learn Proven Frameworks for Better Product Decisions

Understanding cognitive biases is the first step. The next is mastering the frameworks and discovery techniques that counteract them systematically. Our Building Innovative Products Workshop teaches the proven product principles used by market leaders like Google, Apple, and Netflix to build the right products using evidence-based decision-making.

Over two intensive days, you’ll learn practical frameworks for customer discovery, assumption testing, and validation that address confirmation bias, overconfidence, and the other biases covered in this article. You’ll leave with ready-to-use templates and tools you can implement immediately to make better product decisions and deliver breakthrough customer value.